- Home

-

Country Level Data

- East Asia & Pacific

- Europe & Central Asia

- Latin America & Caribbean

- Middle East & North Africa

- North America

- South Asia

- Sub-Saharan Africa

- Attributes

The Digital Trade and Data Governance Hub seeks to better understand what nations are doing to govern data and help others assess the principles, policies, standards, laws, regulations, and agreements designed to control, manage, share, protect, and extract value from various types of data. For many governments, governing various types of data has become an essential, albeit challenging, task, requiring new strategies, structures, policies, and processes. Moreover, data governance is fluid, reflecting societal and technological challenges as well as the will, understanding, and expertise of both policymakers and the broader public.

In 2021 the Hub designed a new evidence-based metric to characterize a comprehensive approach to data governance at both the national and international levels. We divided data governance into six attributes (the dimensions in which nations act as they govern data) and subdivided these six into 26 indicators specific evidence of action. We then used the metric to assess 51 countries plus the European Union. We selected nations from different regions of the world, varied levels of digital prowess, and different levels of income. After examining evidence for each indicator, we graded each nation on its performance. The map below indicates total scores for each of the 51 nations and the European Union.

* We define comprehensive data governance as a systemic and flexible approach to governing different types of data use and re-use. We believe that policymakers are constantly working towards an approach that can simultaneously empower individuals, groups, and firms; protect individuals from harm; meet changing societal and technological conditions; and plan for and grapple with the side effects of data-driven change.

* We encourage readers to compare countries, but we do not intend the scoring to be used as a ranking of data governance quality or effectiveness.

* Colors represent countries' overall score on the DataGovHub Metric.

Swipe Across for More

All of our case studies are governing data, but many high and middle-income nations have made significant progress in data governance. Chart 1 shows that some countries, like the United Kingdom and Germany, perform well across all attributes. At the same time, nations such as Iran, Ethiopia, and Bangladesh are just beginning to adopt data governance policies, processes, and structural changes. Moreover, the 16 highest-scoring countries are all high-income countries with the prominent exception of Brazil (see Table 1). Most of the high-performing countries are located in Europe.

| Attribute | Indicators | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) Strategic | 1(a) Data Strategy | 1(b) Public Administration Data Strategy | 1(c) Federal Guidelines for Private Sector Data Sharing | 1(d) AI Strategy | |

| (2) Regulatory | (2a) Personal Data Protection Law | (2b) Open data law for the proactive release of government information by default | (2c) Freedom of Information Act | (2d) Right to be Protected from Automated Decision-Making | (2e) Right of Data Portability |

| (3) Responsible | (3a) Data Charter | (3b) Public Sector Data Ethics Framework | (3c) AI Ethics Framework | (3d) Trust Framework for Digital Identity Management | |

| (4) Structural | (4a) Personal Data Protection Body | (4b) Open Data Portal | (4c) Open Data Body | (4d) Public Sector Data Governance Body | (4e) International Data Affairs Body |

| (5) Participatory | (5a) Public Consultation on Personal Data | (5b) Public Consultation on Public Data | (5c) Expert Advisory Body on Data Ethics | (5d) Expert Advisory Body on Data-Driven Technical Change and its Impact on Society | |

| (6) International | (6a) Convention 108+ | (6b) Open Government Partnership | (6c) OECD AI Principles | (6d) Binding Trade Agreements on Cross-Border Data Flows | |

Table 3 reveals three areas of convergence based on the prevalence of several indicators. First, more than 84% of the 52 nations studied have adopted Freedom of Information Acts and Open Data Portals. Our analysis here is not surprising; citizens have long pressed for access to information and open public data. Second, most nations (some 70%) have adopted personal data protection structures and regulations. Third, many governments have adopted AI strategies, reflecting the import of AI to the data-driven economy as well as public concerns about its use for decision-making.

| Indicator | Attribute | Percent of Countries with This Indicator |

|---|---|---|

| Freedom of Information Act | Regulatory | 92% |

| Open Data Portal | Structural | 84% |

| AI Strategy | Strategic | 71% |

| Data Protection Body | Structural | 71% |

| Public Consultation on Personal Data | Participatory | 69% |

| Personal Data Protection Law | Regulatory | 69% |

Although most of our countries have laws governing public and private sector use of personal data (37 out of 52), these laws vary in scope. For example, China and Malaysia have passed data protection laws that limit the private sectors’ use of personal data but these laws do not cover the government’s use of personal data. India is debating similar exceptions for the government. While the U.S. does not have one comprehensive federal law protecting private use of personal data, it has laws governing public sector use of personal data.

We found evidence that policymakers are adopting novel and innovative approaches to emerging challenges such as how to encourage trustworthy data-sharing. We also found that we must frequently update what countries are doing to keep pace with new developments. For example, while we were writing this report, Saudi Arabia approved a new data protection law.

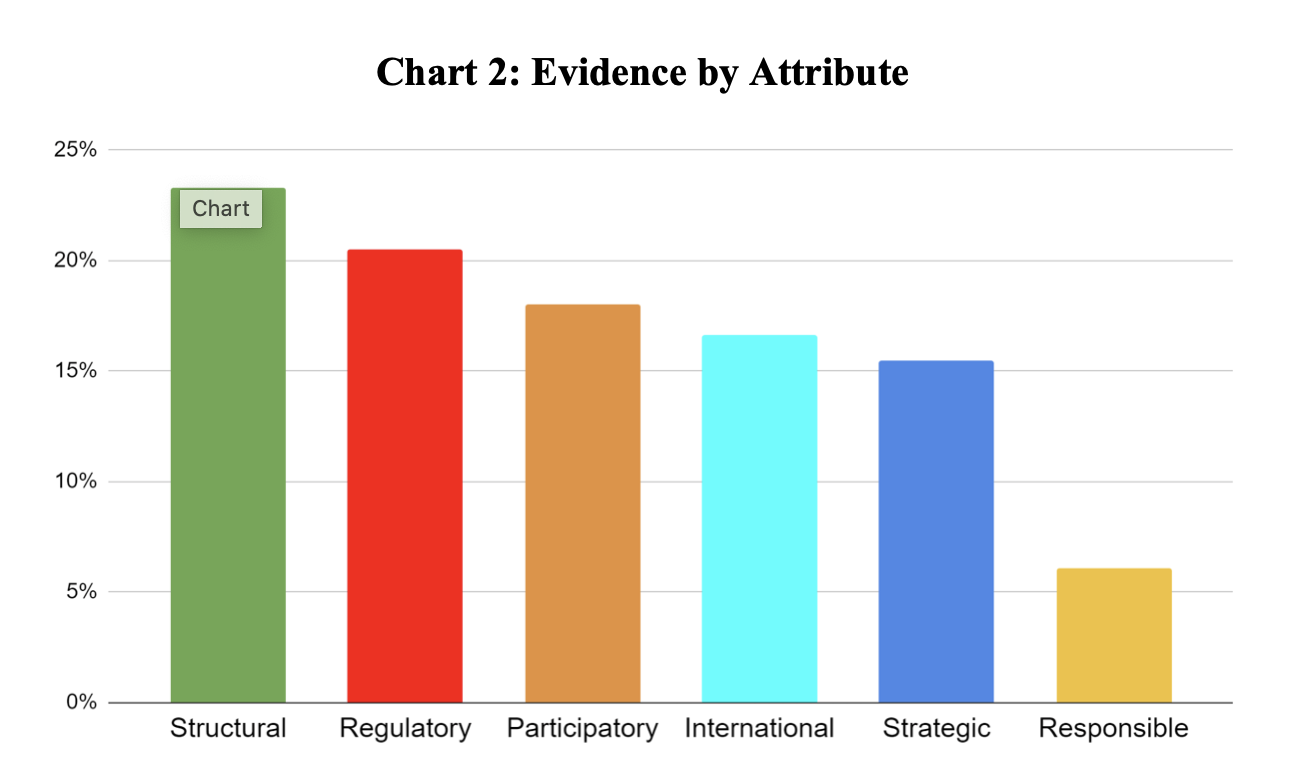

Nations are doing more to Regulate and Adapt Governance Structures than to Develop Participatory and Responsible Approaches. As Chart 2 shows, we found more evidence that our 52 nations are taking action in the attributes of structure and regulation than in those of participation and responsibility.

We found considerable evidence that governments ask for comments from their constituents on data governance strategies, processes, and structures. But we were unable to measure if citizens actually commented and if those citizens truly reflect a diversity of views within the country. Moreover, we could not ascertain the extent to which governments 'heard’ these comments and make changes in response. However, because so much human activity has moved online, data governance has become an essential governance responsibility. Hence, we believe that policymakers must make major efforts to educate and involve their citizens in data governance.

Data governance is a work in progress for every one of our case studies. Almost every case study nation has put in place laws, regulations, and/or executive orders to govern all three types of data.

No nation seems close to comprehensive data governance, which we define as a systemic and flexible approach to govern different types of data use and reuse. Such a system regulates government as well as private sector use of personal and proprietary data and empowers users.

Significant convergence on personal data protection laws: Fifty one (or 98%) of our case study countries had a personal data protection law; only the UAE did not. Moreover, 64 percent of our cases had adopted a comprehensive approach to personal data protection, which we defined as covering private and government use of data, informed consent, an agency to enforce the law and rules governing 3rd party transfer or sale of personal data.

However, higher income countries did not have the mostcomprehensive approaches to personal data protection. Several high income countriessuch as Taiwan and New Zealand do not mandate informing data subjects when their data is transferred or sold to a third party. We also find that many of the mechanisms used in personal data protection that were popularized by the EU are now being put into law in other parts of the world.

Major convergence on public data governance: Over 80 percent of our case studies had an open data law, meaning that in general data collected, utilized, analyzed, and funded by the case study government was made open for its citizens and others to utilize. However, many nations, including low income developing countries, are still figuring out how to govern public data and make it useful to their constituents, whether for research or business purposes. Consequently, 48 percent do not mandate such data be provided in a machine readable format which makes it easier to use and reuse.

Some convergence on proprietary data governance: 76 percent of our cases had enacted a trade secrets law and 80 percent of our cases participated in an international trade agreement with trade secrets provisions. However, we found some evidence that governments were pushing back against firm control of data use and reuse. For instance, 47 percent of nations with a trade secret law did not give firms using data analytics explicit control over data they analyzed using a mechanism protected under trade secrets, while 52.9 percent of nations did give these firms such control.

Significant convergence on data governance in trade agreements: 77 percent of our cases participated in a trade agreement with provisions encouraging electronic authentication and e-signatures; 71.2 percent participated in an agreement with aspirational language to encourage interoperability of privacy regimes; and 78.8 percent with aspirational language on cyber-security.